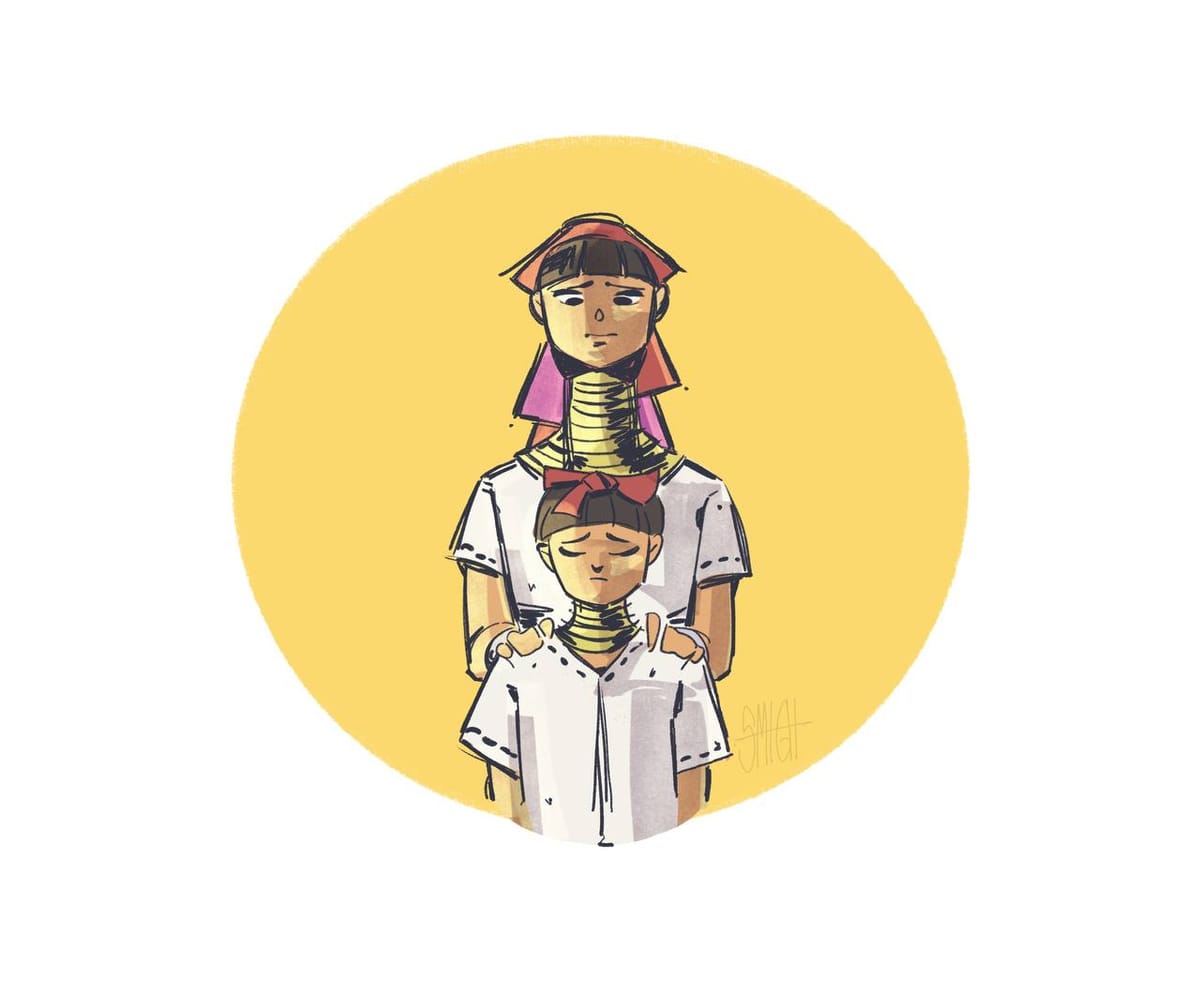

Is paying to observe someone's daily life and culture a valuable cultural exchange, or is it human exploitation? In today's society, where even traditional zoos are being criticized for violating animal rights, ethnic-based tourism has become increasingly controversial.

The "long neck villages" in Thailand's Mae Hong Son district, which face criticism as "human zoos," are at the center of this debate. It costs about 74 USD per person to visit these villages through tour packages. If you arrange your own transportation from Chiang Mai by motorboat, the village entry fee ranges from 300 to 500 baht per person.

These villages are home to ethnic groups who maintain lifestyles, customs, and cultural practices largely isolated from the modern world. Without electricity or modern amenities, living as they did before the industrial era, visiting these villages feels like stepping into a separate universe.

However, the residents of these villages are not Thai ethnic minorities but Kayan people from Myanmar. Why are Myanmar's Kayan people here? Why have they become tourist attractions in Thailand's tourism industry?

This complexity makes these villages a major focal point in the ongoing debate about whether they constitute human zoos.

The Beginning of Mae Hong Son

Starting in 1984, Kayan people from Kayah State began migrating to Thailand in large numbers. There were multiple reasons behind this migration.

Under the Myanmar military government's "area clearance" operations, many ethnic villages were destroyed. The Kayah State's ethnic groups also suffered from the military's "Four Cuts" strategy. Regional instability, military operations, extortion, forced portering, and threats to economic and social survival became the driving forces behind their mass exodus.

When leaving their homeland, Thailand's northern Mae Hong Son district, with its proximity to the border, became the most suitable destination for relocation. Thai authorities took notice of the Kayan refugees entering their territory.

The distinctive appearance of Kayan women with their long necks caught the attention of Thai authorities. They conceived the idea of ethnic-based tourism centered around the Kayan women's brass coil tradition. Thus, the project began in 1985.

Rights Within the Kayan Village

When the tourism project started, the first step was establishing a dedicated Kayan village in Mae Hong Son. Land was provided free of charge. They were allowed to build traditional houses and sell their handmade traditional clothing and crafts. Healthcare centers were established for basic medical care, and hospital treatment was provided for major health issues like childbirth and serious illnesses.

Primary schools were opened for children's education. Those wanting to pursue secondary education could attend schools anywhere in Thailand.

Additionally, monthly allowances were arranged for the Kayan people. Those above 12 years old receive 1,500 baht (approximately 200,000 Myanmar kyat), while those under 12 receive 750 baht (approximately 100,000 Myanmar kyat). However, these allowances are only given to women who wear brass coils. Kayan men do not receive any allowance.

Residency cards, both blue and green, were issued. Blue cards were for Kayan people who settled in Thailand before October 3, 1985, while green cards were for those who arrived after. These cards are similar to guest citizenship cards but don't allow voting rights and have travel restrictions. Children born to parents holding these cards are recognized as Thai citizens and can pursue education beyond Mae Hong Son.

Restrictions Within the Kayan Village

Since the tourism program is based on the brass coil tradition, all Kayan women in the village, from children to elderly, must wear brass coils. They must wear them both in the village and when going outside. This is a strict rule without exceptions.

Besides wearing brass coils, they must wear complete traditional clothing and speak only their native language. Even if they know Thai, they're not allowed to speak it. A Kayan woman risks arrest if she leaves the village without brass coils or traditional clothing.

Travel to places like Bangkok and Chiang Mai is only permitted during government-organized tourism promotion trips. Regular travel is not allowed.

Only about 30% of Kayan people have the government-issued residency cards. Most hold migrant worker cards. Thus, not only are Kayan women restricted, but most Kayan men are also limited in their movement. Only a small number with residency cards can freely pursue work. Most men work in nearby farms or help with traditional handicrafts.

Living conditions in the village must strictly follow traditional ways. There's no electricity or modern amenities. Contemporary technology and modern lifestyles are specifically prohibited in Kayan villages. Since the villages showcase the distinct customs and traditional lifestyle of Kayan people, they must maintain their ancient way of life to keep attracting tourists.

This is somewhat similar to the conservative Amish in America. However, while the Amish choose their electricity-free, modern-amenity-free lifestyle themselves, the Kayan people avoid using modern conveniences out of fear of losing Thai government support.

Additionally, Kayan people are not allowed to resettle in third countries. These restrictions have led young Kayan generations and human rights activists to question the Thai government's policies.

The Brass Coils Between Myanmar and Thailand

A Kayan girl living in Myanmar can refuse to wear brass coils around her neck if she chooses. She can move freely without wearing brass coils. However, Kayan girls living in Mae Hong Son villages absolutely do not have this freedom.

The brass coil culture of Kayan women, which has captivated the world, has existed for over 900 years. According to the research journal "Genealogical Records of the Kayan Nation" published by the Kayan Social Organization, the brass coil tradition dates back to the Bagan period around AD 1070, during King Anawrahta's reign.

The Kayan people believe they are descendants of dragons, and they wear multiple brass coils around their necks to resemble their dragon mother. Besides this dragon lineage belief, there are alternative narratives suggesting they wore brass coils to protect themselves from Burmese kings' conquests during the monarchical period or from dangerous predators like tigers.

Despite these varying interpretations, Kayan women consider wearing brass coils a cherished heritage to be maintained until death. It's viewed as a standard of beauty - the longer the neck, the more beautiful.

However, in modern times, the brass coil culture has faced conflicts with contemporary life. These distinctively different brass coils have become obstacles to modern living. Besides facing unusual stares, some generations have begun to view this as a form of restriction.

Consequently, in Myanmar, Kayan women wearing brass coils are mostly elderly, and they can only be found in Pan Pet village in Demoso Township. Brass-wearing Kayan women have become extremely rare in Myanmar.

If you want to see brass-wearing Kayan women, you might even have to go to Thailand. While the brass coil tradition is fading away in Myanmar, it remains firmly established in Thailand and has become a heritage that generates significant foreign currency.

It's impossible to make a simple judgment about whether this disparity is good or bad. These brass coils represent a complex situation. Despite accusations of human rights violations and treating humans like zoo animals, there's no clear solution to this issue.

During the COVID period when the tourism sector was severely impacted, Mae Hong Son's Kayan people returned to their homeland. They attempted to settle back in their native land and start traditional businesses and tourism ventures, just as they had done in Mae Hong Son.

Everyone is happiest in their birthplace. Everyone wants to live freely in their own land and water. The Kayan people were once powerful and lived with historical tradition.

The Lost Land

Kayah State, known as Karenni, was once an independent region with self-governance. In the 1875 alliance treaty signed between the Myanmar King's representative, Kinwun Mingyi, and the British India Viceroy's representative, Sir Douglas Forsyth, Karenni State was designated as a separate independent territory.

After independence, under the effects of civil war and successive military governments' ethnic oppression, Karenni ethnic groups' traditional culture and survival became increasingly threatened, ultimately leading to their displacement.

During the civilian government period and the dawn of democracy, hope was renewed. Kayan people from Mae Hong Son returned and reclaimed their homeland.

However, when the wave of the military coup hit, Kayah State, once known as Karenni, became one of the earliest conflict-affected regions. The Kayan people's Karenni dream was once again destroyed, and they returned en masse to Mae Hong Son.

The Thai government arranges tourism programs as a price for providing the Kayan people with residency and security for their lives and property. While this might seem exploitative, for displaced Kayan people, it might be the safest option. Myanmar doesn't currently offer sufficient guarantees for their security, economy, and children's education if they return.

Last April, four Kayan villages in Mae Hong Son district combined to celebrate their first traditional pole festival. Conducting their traditional festival on rented land demonstrates both their resilient unity and a fading dream of returning home.

The brass-adorned Kayan necks in Mae Hong Son remain an unsolved puzzle for the world. You can see them in Thailand for 500 baht. Whether to view people being displayed like a human zoo is a matter of personal conviction.

By Nu Thit Moe (Y3A)

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar-Media : Insights | Empowering Myanmar Youth, Culture, and Innovation

Build Myanmar-Media Insights brings you in-depth articles that cover the intersection of Myanmar’s rich culture, youth empowerment, and the latest developments in technology and business.

Sign up for Build Myanmar - Media

Myanmar's leading Media Brand focusing on rebuilding Myanmar. We cover emerging tech, youth development and market insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Sign up now to get the latest insights directly to your mailbox from the Myanmar's No.1 Tech and Business media source.

📅 New content every week, featuring stories that connect Myanmar’s heritage with its future.

📰 Explore more:

- Website: https://www.buildmyanmarmedia.com/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/buildmyanmar

- YouTube: https://youtube.com/@buildmyanmarmedia

- Telegram: https://t.me/+6_0G6CLwrwMwZTIx

- Inquiry: info@buildmyanmar.org

#BuildMyanmarNews #DailyNewsMyanmar #MyanmarUpdates #MyanmarNews #BuildMyanmarMedia #MyanmarNews #GlobalNews #TechNewsMyanmar #BusinessNewsMyanmar #Updates #Insights #Media